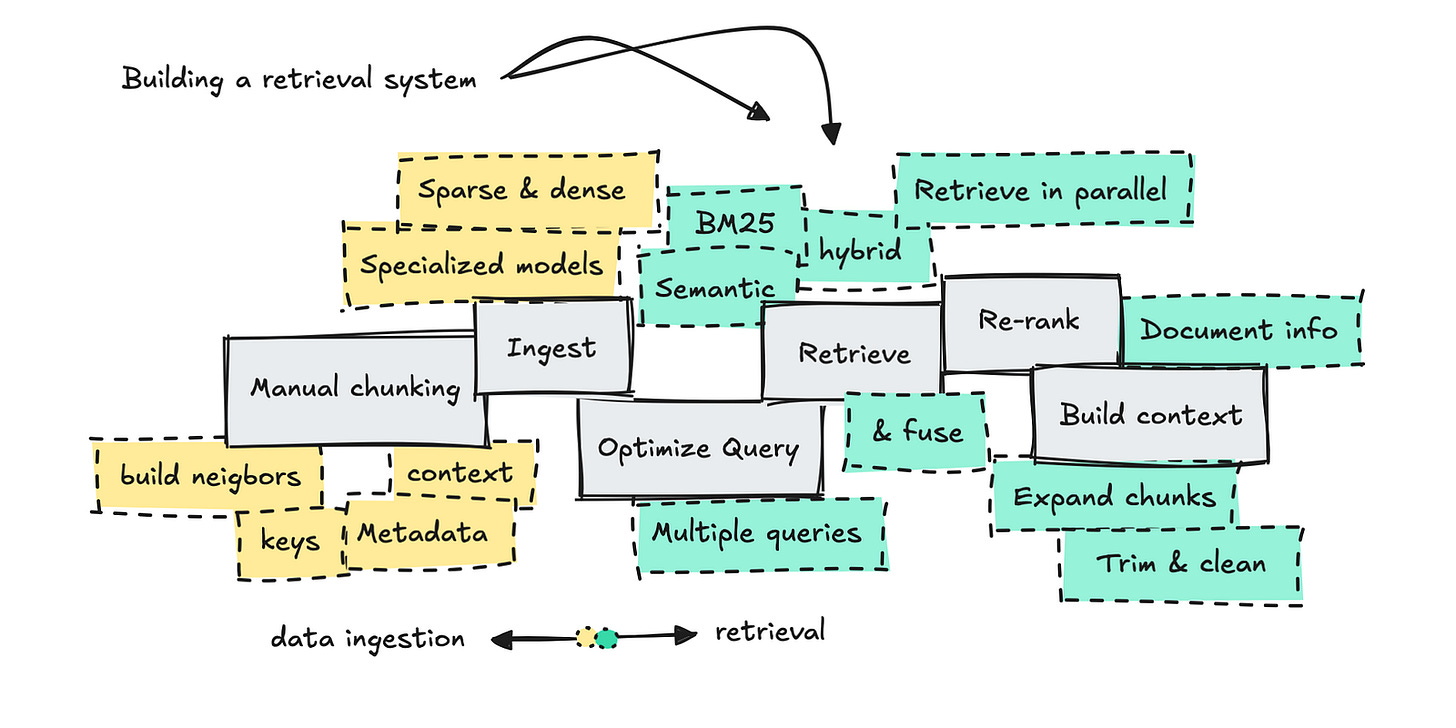

Designing Your Retrieval Stack

Four Techniques and Their Tradeoffs

A few weeks ago, I wrote a post with my friend Adam Gurary from Databricks about how different UX surfaces have different retrieval budgets. The idea was basically that retrieval systems depend on user experiences, specifically how much latency users expect.

Different UX surfaces have different latency expectations. A few examples:

Type-ahead search (autocomplete) is very latency-sensitive. Users expect results to update on every keystroke. If there’s any visible delay, users just keep typing, abandoning the feature entirely.

Traditional search results (internal tools, dashboards, enterprise search) allow for some delay, especially if relevance improves.

Conversational agents and chat interfaces allow for the most delay of these three. In fact, users expect thinking time and delays are generally associated with better results.

In our conversation, Adam argued that a common mistake he sees teams make is assuming that layering in more retrieval techniques automatically leads to better products. It doesn’t. Every additional retrieval stage adds latency, compute cost, operational complexity – and new failure modes, some of which can be hard to detect. Understanding what latency your UX can support is important in deciding when it makes sense to layer in more retrieval techniques.

Below are four commonly used retrieval techniques and the latency tradeoffs associated with each.

Technique 1: Hybrid Search

Hybrid search combines two complementary approaches: lexical search and vector search.

Lexical search is great when users know the exact words or filters to use. It works well when queries line up neatly with the underlying data. But the downside is that it breaks easily with synonyms or inconsistent terms. If a user’s wording isn’t the exact same as the indexed terms, lexical search will return nothing even if the right document exists. I’ve seen teams spend weeks debugging “missing data” bugs that were really just vocab mismatches.

Vector search, on the other hand, matches semantic meaning instead of exact words. It therefore doesn’t break with messy or underspecified queries. This makes it better at capturing intent when users don’t know the right terms. But the downside is noise. Semantic similarity can be fuzzy because embeddings blur small distinctions.

With hybrid search, you’re now running multiple retrieval paths instead of one, which adds latency and complexity. This makes it less viable for super low-latency UX interfaces, such as autocomplete.

Technique 2: Re-ranking

Re-ranking is one of the most effective tools in retrieval. It improves relevance by running a broad first-stage retrieval (using lexical search, vector search, or both), then taking the top N candidates (often 20 to 200 documents) and passing them through another model to re-order them by relevance. That second-stage model is usually a more expensive model, and evaluates each candidate in the context of the full query instead of comparing embeddings in isolation.

One of the reasons re-ranking is so valuable is that many organizations embed almost identical-looking content so they get back almost-identical looking pages in return. These pages might differ in just a few words, but those are the important words – a version number, jurisdiction, exception, or clause. Re-ranking helps detect these small but key differences. Document improvement (i.e. how do you chunk your documents, what snippets/ai-rewrites do you actually embed and retrieve against) can help a lot with re-ranking.

Re-ranking is important for standard retrieval pipelines and especially useful where the rank order of results determines what the system actually sees such as question answering, recommendations, or agent decision-making.

The potential downside is that it adds tens or hundreds of milliseconds of latency, and compute overhead. Also, if the re-ranking model mistakes what should be ranked higher, it will promote the wrong results.

Technique 3: Query Rewriting and Expansion

Users are usually bad at asking good questions. Query rewriting tries to fix this before retrieval starts. Instead of taking the user’s input at face value, the system takes a step back and asks: what is this person probably trying to do? Then it retrieves against that interpretation instead of what the user typed. This usually means clarifying, adding context, or creating multiple related queries that explore different possible meanings of the original input.

This technique is really useful in conversational systems, where queries are naturally messy and context accumulates. By expanding the search space, query rewriting can improve recall and downstream answer quality.

Query rewriting, however, adds additional model calls, increases latency, and makes retrieval pipelines harder to debug. It also introduces the possibility for semantic drift.

Technique 4: Larger Embedding Models

Larger embedding models can capture richer semantic meaning, subtler distinctions, and deeper domain context. In jargon-heavy or highly specialized industries, this is useful.

Improvements in recall come from expressiveness. Larger models can better encode relationships between concepts that smaller embeddings often ignore. This makes them better at surfacing content that doesn’t necessarily look similar, which is valuable in exploratory or conversational retrieval scenarios.

For example, an industrial maintenance company might look to help answer technicians’ questions such as “what are early indicators of spindle failure?” But the most relevant documents in the corpus likely don’t use any of those words or phrases – instead the documents probably reference harmonic vibration patterns, bearing preload drift, and thermal creep. Larger embeddings can link all of these related concepts.

Unsurprisingly, larger embedding models are slower to run and require more latency, memory and storage.

Designing Retrieval Backwards From UX

Retrieval is a series of tradeoffs. The same technique might be useful in one product but actively harmful in another. A product or system might not fail because it lacks intelligence, but because it has too much of it. Knowing what users expect and will tolerate is a good starting point when thinking about designing your retrieval stack.